NOTE: This article was originally written in March 2024, for undisclosed reasons, I didn’t publish it at that time. SolarMarker’s infrastructure went defunct in 2024. This malware doesn’t appear to be an active threat, but this article is to discuss means of investigation for similar threats, or if SolarMarker returns. The post has been updated to reflect the current state of the malware.

Abstract

SolarMarker malware was a common threat but nothing had been published or widely shared about the actor’s actions or objectives—until now. Based on original findings from monitoring an infected computer for months, this blog-post discloses—for the first time—the financial fraud carried out by the SolarMarker actor group.

In this blog-post, we will introduce SolarMarker—highlighting the Virtual Network Computing (VNC) component which allows threat actors to connect to a victim device and load the victim’s browser data as their own. With the browser data loaded, threat actors can access accounts to perform financial fraud and data theft. This type of fraud is known as on-device-fraud.

Who or what is SolarMarker?

In this post, we refer to both the malware and the actors as “SolarMarker”. We apologize for any confusion, but we trust that context will clear up any confusion. The actors consist of the following: a developer who maintains the software and affiliates who leverage remote access to victim hosts to commit fraud.

SolarMarker as a malware was first seen in July 2020. The malware has always consisted of multiple modules. The modules are primarily named after planets using the Russian spelling:

- Jupiter (Russian: Jupyter) – an infostealer module

- Mars – a backdoor module

- Uranus (Russian: Uran) – a keylogging module

- Saturn – a VNC module

- FG – a form-grabbing and crypto-wallet stealing module

- SOCKS – this is a SOCKS proxy module

These modules have always existed, but have not always been in use.

We take this opportunity to clarify the following: SolarMarker’s primary purpose has been on-device-fraud. SolarMarker was mistakenly classified as an infostealer due to its infostealing module, however, the infostealing module always existed alongside the other capabilities. The essential function of the infostealing module has been to profile the device—giving attackers an understanding what accounts they would have access to when using the VNC client. Similarly, the VNC client has always been a core-component of the malware. The developer originally used a fork of hidden VNC (hVNC) and then he wrote his own VNC client.

To emphasize again, the maintainers of SolarMarker didn’t sell credentials like actors who focused on credential stealing would. Further, with stolen credentials, an actor needs to attempt to access accounts from another device, but with SolarMarker, the affiliates are able to leverage the credentials using the victim’s device.

Gaining Insight

To discover this behavior, we set up a domain and self-infected a host, we then monitored the infected host for months. We infected a host in both 2022 and in 2023.

In 2022, the threat actor deployed multiple payloads onto our infected host without any obfuscation: this helped provide a basic understanding of common payloads. We were able to see plainly how the VNC module was loaded: The VNC process has regularly been injected into a Windows process. The VNC client would run from within that process. At that time, we learned that the VNC client was capable of loading the victim’s browser, however, we were unable to determine how that access was leveraged.

In 2023, we put live credentials in the browser and monitored activity. We then observed the attacker perform the following actions.

Actions Performed

- Attacker attempted to log into banking accounts. (No valid account was provided.)

- Attacker attempted to log into Amazon accounts. With a valid account, they reviewed the credit cards, gift cards, and addresses associated with the account.

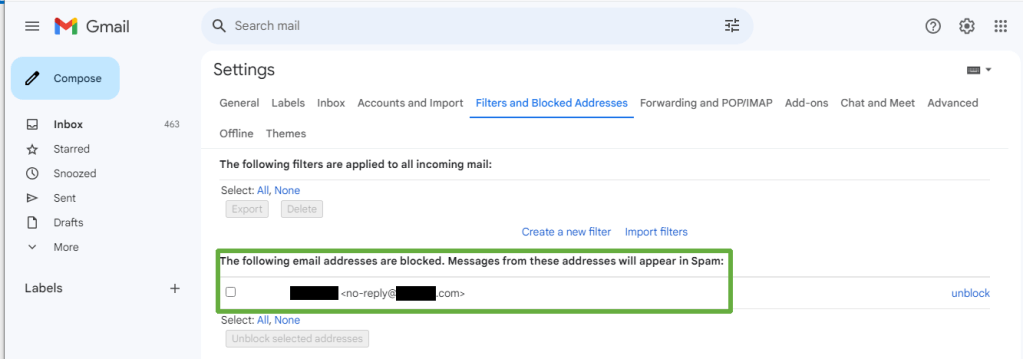

- Attacker accessed victim’s Gmail account. Attacker reviewed settings and addresses associated with the account. Attacker reviewed emails in multiple inboxes. Attacker stole financial information from the sent box.

- Attacker attempted to purchase items such as a Google Pixel phone. (There were insufficient funds at the time of the attempt.)

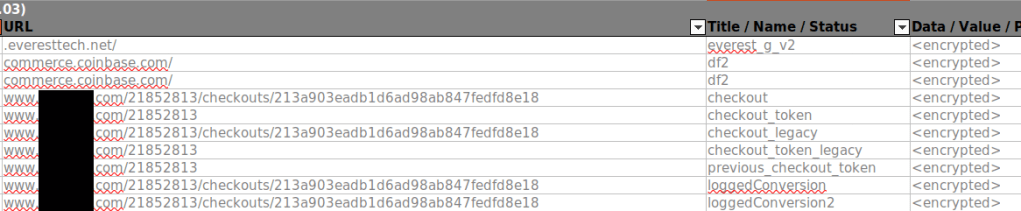

- Attacker accessed victim’s Coinbase account. Attacker reviewed settings for the account and made purchases.

- Attacker set inbox rules in Gmail to hide emails associated with purchases.

- Attacker deleted emails associated with purchases manually.

- Attacker returned and deleted inbox rules to cover tracks.

All of these actions were performed from the victim device and were made possible due to credentials stored by the browser and by accounts that were logged in at the time of access. We were able to monitor all of these activities due to them being performed from the device. Using the victim’s device makes the reporting of fraud difficult, as a result, it is important for victims to know how to detect this malware. We recommend reviewing our previous blog-posts (such as this one) or even contacting us to confirm indicators of an infected host to support fraud reports.

Note: The VNC client is also capable of loading content from Outlook clients, but we did not monitor for this activity in our configuration.

Viewing the actions

The following will explain how this visibility was possible.

Note: Some information in the following images are redacted only because the SolarMarker developer reads these blogs. If you need or want more information, contact me.

When a host is infected, the backdoor will launch on startup. After about 30 minutes, devices in the designated VNC group will receive the VNC client as a payload from the backdoor. The VNC client is injected into the memory space of a legitimate Windows process. In 2022, the process was “GamePanel.exe”. From 2023 through 2024, the process was “SearchIndexer.exe”; however, the process used is likely to change after this publication based on the developer’s attempt to avoid detection. Regardless of the process used, the behavior will be similar.

The image below is a screenshot of Process Hacker displaying the behavior. In the process tree, the running PowerShell was the persistent backdoor which loads the VNC client into SearchIndexer.exe. With the VNC running from SearchIndexer, it loads a copy of the victim’s browser data as seen in the command-line arguments by using the option --user-data-dir=.

The browser data in the image is loaded from a directory in the “Temp” directory and contains the same contents as the Chrome “User Data” directory. This behavior is consistent with the findings from eSentire‘s static analysis of the VNC client, except that the developer changed the name of the directory after eSentire’s publication.

Once loaded from this directory, all Chromium artifacts are saved in this directory. The actor can interact with the browser from the user’s normal directory (and may need to in some cases, such as when files are locked and cannot be copied) but the majority of their actions occur from the copy in the temporary directory. In either instance, the attacker attempts to cover their tracks by clearing the Chrome History manually by navigating to the Chrome History tab and removing items.

Even when the attacker cleared Chrome History we were able to observe their actions using a more fragile forensic artifact: Chromium Session files.

Chromium what?

Chromium is the open-source basis of many modern browsers: Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Brave, and many others. Chromium stores user activity into a file called a “Session file”. A Session file starts when a user opens a new window and it documents all activity performed by the user in that window: the opening/closing of tabs, the forward/backward navigation, and more. The purpose of Session files are to provide a good user experience: they allow a user to re-open a window and it allows that window to have the same behavior as if the user never closed it.

So while the attacker cleared their history, the activity of their Sessions were still accessible.

Chromium Sessions are a under-appreciated forensic artifact. Fortunately, I maintain a tool for parsing Chromium Session files: Chromagnon. (Credit for the original project goes to JRBancel, I forked the project and added substantial updates due to changes to Chromium in the last 15 years. JRBancel had established a solid foundation.)

The following is an example of the output from the investigation:

UpdateTabNavigation - Tab: 826756992, Index: 2, Url: https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#trash

UpdateTabNavigation - Tab: 826756992, Index: 3, Url: https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#trash/FMfcgzGxSHfcQkLVxKXpDSdbJdsxMDNr

UpdateTabNavigation - Tab: 826756992, Index: 4, Url: https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#trash

UpdateTabNavigation - Tab: 826756992, Index: 5, Url: https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#settings/general

UpdateTabNavigation - Tab: 826756992, Index: 6, Url: https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#settings/filters

In this snippet the actor did the following: They navigated to the trash. They opened a specific email. They returned to the trash. They navigated to the “general” tab of the settings. They navigated to the “filters” tab.

From these actions, we infer the following: they deleted an email, they then went to the trash, opened the same email and deleted it permanently. After deleting it, they set up a filtering rule to filter future emails. Since the Session file provides us the URLs associated with activity, we can confirm these details by navigating to the same pages. Indeed: we were able to confirm that the email with that id no longer exists and that a filtering rule was configured.

We were also able to confirm that funds were spent from the Coinbase account.

While Session files gave us a great deal of visibility, they are fragile. Usually only a few are stored at any time. In this instance, we missed what exactly was purchased. We used Hindsight to parse the entire user profile used by the attacker. From the output of Hindsight, we were able to see additional context regarding their purchase.

In addition to the fragility from only a few Session files being stored, the attacker copies the victim’s profile into the temporary regularly which overwrites existing files. As a result, we had to diligently copy the User Profile from the Temporary directory to preserve all the artifacts. We don’t believe that it is practical to rely solely on this artifact in a production environment. However, it does help reveal the most recent activity and in this situation, helped us establish clear insight into the activity performed by the actor.

Detection Recommendations

If you are interested in detection opportunities, please write to us and they will be shared privately. If we were to publish them, the threat actor would change details as to undermine the detections. Even though the malware is currently inactive, I’m taking this precaution.

Conclusion

In this blog-post, we disclosed what we believe are the most important elements for victims: namely, that the SolarMarker backdoor is leveraged to perform on-device-fraud and steal arbitrary information from email.

We recommend being familiar with SolarMarker’s indicators both for defense and for incident response for when infections and fraud occur. This tactic of on-device fraud was seen in 2012, so it isn’t particularly new, but it is important to recognize it still occurs.

With actions-on-objectives having been disclosed, we believe others are now better able to accurately assess the risk of SolarMarker malware in their environments.