Image caption: My drawing of an Among Us character with VirusTotal certificate details for a SolarMarker loader. File details are user defined. Usually the details are serious, but some have fun with it.

Introduction

In 2023, I presented at SLEUTHCON regarding authenticode certificates (also known as code signing certificates) which were issued to an impostor (video presentation, blog-post). That presentation focused on the investigative finding that one code signing certificate is often leveraged by multiple threat actors. This was demonstrated by reviewing more than 700 binaries which used 1 of 50 certificates known to have been used by the SolarMarker malware developer and finding binaries from 15 malware families.

That research was originally inspired by a 2018 scholarly article which argued that using an impostor to acquire certificates was the becoming the primary method that malware was signed. I refer to these certificates as “impostor certs”, and because of Among Us: “suspicious certs”. (If you missed the Among Us fad, the important thing to know is that the game requires players to identify impostors that look like the other spaceship crew mates. The red character in this blog-post is an Among Us character.)

Since 2023, I have documented another 50 certificates leveraged by SolarMarker: bringing us to 100 certificates known to be abused by the actor. The purpose of this blog-post is to continue to expand awareness of impostor certs by reviewing the impostor certs used by SolarMarker as a case study.

Why do you keep talking about SolarMarker?

In this post “SolarMarker” is used to refer to both the developer and the malware they deploy. In this post, we are primarily talking about SolarMarker malware because we have hit a milestone of having 100 authenticode certificates that had been used to sign the malware. These certs represent a failure in the system. They represent how actors can abuse the same system repeatedly without being stopped.

The SolarMarker developer has had no discernible problem acquiring new certificates. Their sources of certificates never dry up. For the last 3 years, the SolarMarker actor has signed their malware, had certificates revoked, and had a new certificate each week they’ve deployed malware.

Focusing on certificates used by one actor helps provide a consistency in the data and it can reveal trends. Trends that we might miss if we just collect random certificates to look at. (Another reason we look at these is because this is the most consistent dataset I have access to. Unlike other researchers, I don’t have access to paid platforms to query and find abused certificates. If someone wants to help me have that access, I’d be happy to dig deeper.)

Note: By limiting our study to this actor, we limit our focus to certificates used by Russian speaking actors. We believe there are likely different trends and behaviors that could be observed in studying other regional communities (such as the American or Vietnamese markets). Other vantage points are also worth study, but are not covered here.

For more about SolarMarker itself, I recommend reading October 2023 SolarMarker which gives an overview of the malware’s delivery and first stage.

What are certificates anyway?

Authenticode certificates are used to digitally sign executables and installers to validate that the file came from a vetted software provider and was not tampered with. The certificates are appended to the end of PE files, Java Jars, included in MSIX bundles, and used with other formats. To prevent or identify tampering, the certificate itself contains a hash of the file which must match the computed hash for the file.

There are two main certificate types, Standard Code Signing and Extended Validation (EV) Code Signing. The vast majority of certificates used by threat actors are EV certificates and these will be the focus of this post. These certificates require additional validation and represent a higher level of trust.

How exactly does an impostor get them?

Certificates are acquired through the following process:

- An impostor chooses a business to impersonate. They can pass the first stage of certificate validation process if the business is in a government database.

- They register a related domain which they will use for domain validation. The impostor may set up an email associated with the domain to “show” they are part of the business.

- They receive a phone call to validate that they are associated with the business. This will be an attacker supplied phone number. The phone call may be a robocall or a scripted call.

In this blog-post, we will not explore this process in depth. To understand it deeper, I recommend ReversingLab’s article on Executive Impersonation where they follow a specific example.

Once the certificate is acquired, the imposter will sign malware on behalf of malware developers.

Who is being impersonated?

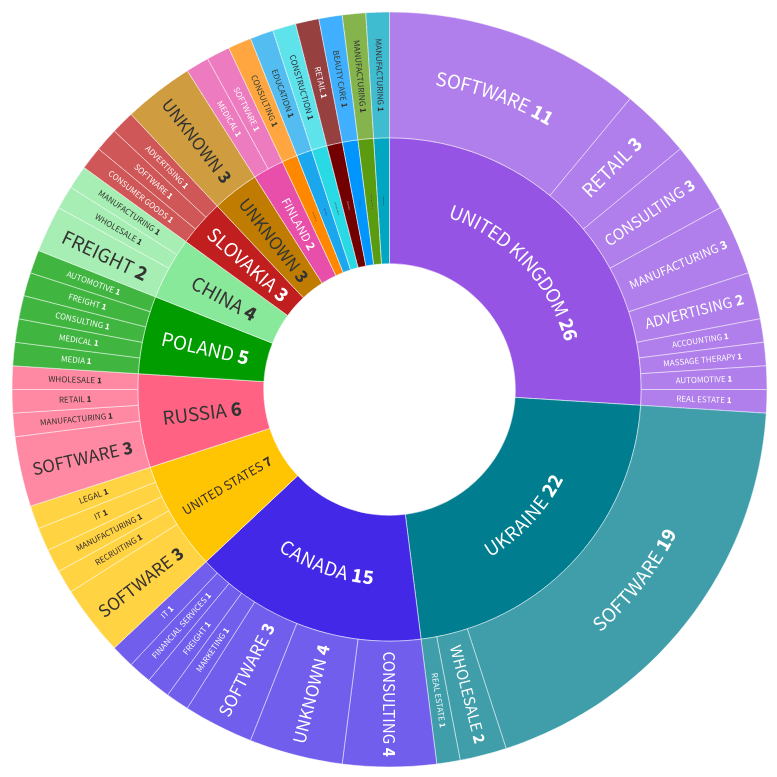

Organization Country

The following sun-burst graph shows the organization’s country and industry for the 100 certificates. (In the interactive version, clicking the sections will expand the category to make it more readable.)

Certificates were issued most frequently to organizations in these countries: The United Kingdom, Ukraine, Canada, the United States, and Russia. At least for this threat actor, certificates for organizations in western and English speaking countries were the most desirable. This is consistent with their targeted victims residing in North America. However, we believe the country associated with the certificate is primarily dependent on what is available from suppliers. The use of Ukrainian certificates deviates from the use of western/English speaker certificates but the Ukrainian certificates (and their use) deviated from the norm in other ways too.

The certificates issued to companies in Ukraine were the most suspicious of the certificates reviewed. Most of these companies were registered in Ukraine from September – November 2023, were issued certificates, and had the certificate revoked within one or two months. Looking deeper, it can be observed that these companies are shell companies that have about $25 USD of shareholder equity each. Most likely, these companies were registered to individuals without their knowledge. I talked with cultural/linguistic insiders and learned that cultural and economic conditions in Ukraine cause this behavior to be fairly common.

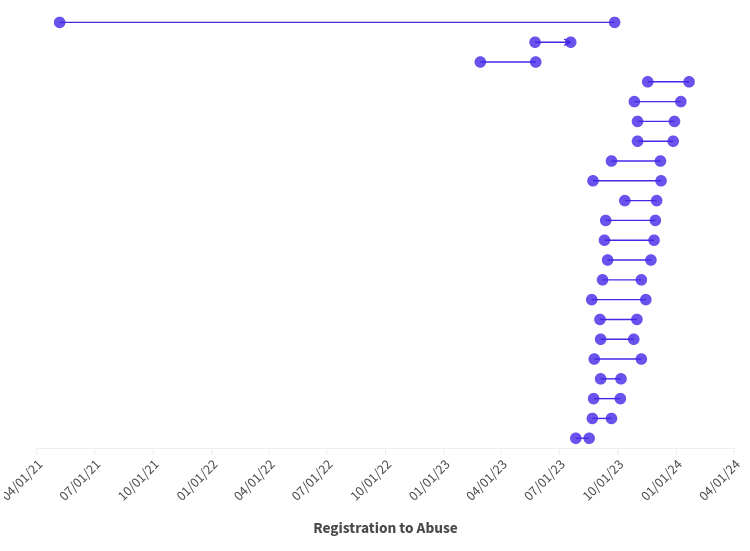

The company registration, the certificate issuance, and certificate abuse all occurred within a small time frame. In the graph below, the left dots indicate the date the Ukrainian company was registered and the right indicates when a certificate for the company was abused. (Note: The company registered in 2021 may have been abused with other malware, but abuse was not reported until September 2023.)

As mentioned previously, the threat actor normally delivered malware with a new certificate once per week, but between September 2023 and January 2024, the developer signed and deployed malware multiple times each week. It is unclear what caused this behavior. Perhaps the circumstances associated with these companies and certificates required expedited use (maybe a special sale from the certificate provider?) or perhaps the actor was attempting a larger number of infections before taking a break from deployments. (The actor took a break from development and new infections January 2024 until March 2024.) No matter the cause, the use of shell companies was abnormal in the dataset. We were unable to discern definite use of shell companies from certificates associated with other countries.

For attackers: the Geo-location, the size, or reputation of the company is relatively unimportant, the only important thing is the trust from the certificate.

Organization Industries

While software companies are often impersonated, the above process of acquiring authenticode certificates does not restrict which company and industry will be impersonated. In fact, it is easier to do domain validation by registering domains for companies that don’t have their own domains; as a result, sole proprietorships and companies who only have Facebook groups are frequent targets.

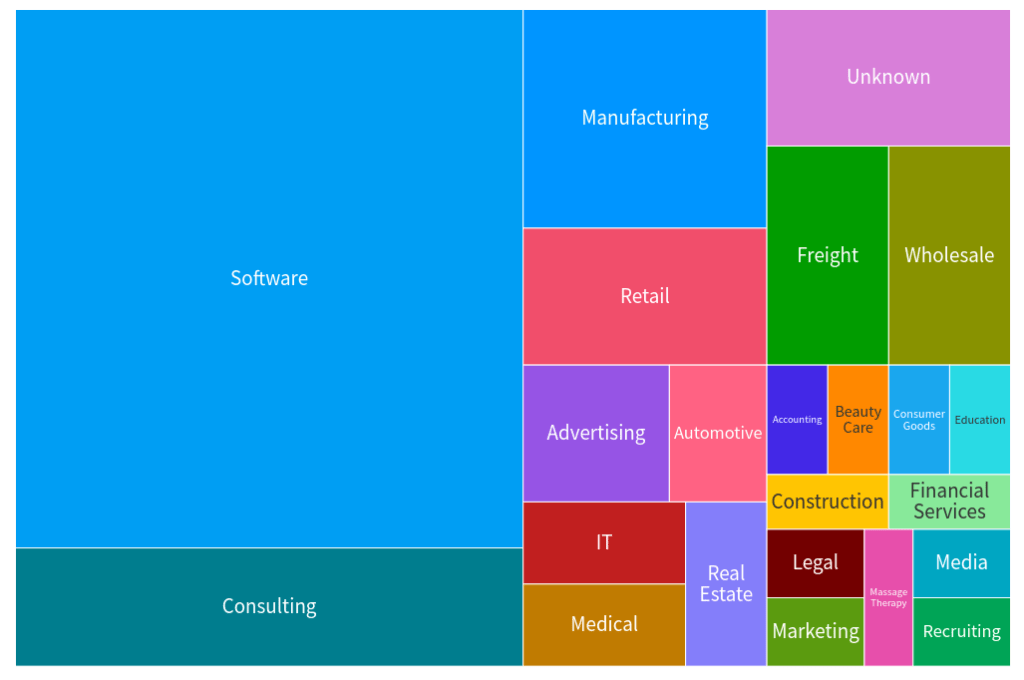

The following tree-graph is a summary of industries identified in the data. The size of each is representative of the number of organizations in that industry:

Software was the largest industry with 41 companies impersonated. (Note: 19 of those were shell companies as discussed above.) Second was consulting. Third, manufacturing. Further down the list, some industries seem more random: automotive repair, a beauty salon, and a massage therapy provider. Again, while organizations in these industries aren’t known for software development, the requirements—mentioned above—do not exclude them from being impersonated.

Response

Certificates are intended to communicate a level of trust that the associated organization is a legitimate software provider, but the system of issuing certificates is heavily abused. When I started as an analyst, I didn’t know authenticode certificates were abused like this: I find that many analysts aren’t aware and I worry that certificate providers aren’t aware either. In general, people don’t seem surprised that there is a problem, but may be surprised at how large the problem is. It is time to change that. It is time to make sure others are aware and report abuse when it is seen.

In this blog, we only looked at certificates used by one malware developer, yet there are many malware developers abusing certificates. The only reason we saw 100 certificates abused was because they were regularly reported, revoked, and replaced. When looking at other malware, many certificates are in use for years. Without revocation malware developers may use the same certificate for a prolonged time or multiple threat actors may use that certificate. Without revocation: awareness, prevention, and response from certificate issuers becomes atrophied too. On the other hand, revoking certificates can impact malware service delivery, can impose financial and development costs against threat actors, and can stimulate improvement in the response processes among certificate issuers.

To facilitate revocation, I’ve released the tool certReport. This tool leverages the MalwareBazaar API so the file needs to be uploaded to the public repository of MalwareBazaar. (MalwareBazaar itself extracts the certificate using ReversingLabs’ A1000 malware analysis platform.) If the file is on MalwareBazaar, the certificate details can be obtained by the API and certReport generates a basic report that includes links to public sandbox analysis reports. certReport also instructs the user where to submit abuse reports. (Finding where to submit them is often the hardest part.) This template should be augmented with additional information from the researcher, but the base report provides the reporter a solid foundation and provides the certificate provider with details they need to conduct their due diligence. In my experience, providing enough context is essential for revocation and many certificates are revoked in less than 1 day.

certReport can be installed using

pip install certReport. Once installed, if the file is signed and uploaded to MalwareBazaar, the user can runcertReport <filehash>to get the report output. Try it with the filehash89dc50024836f9ad406504a3b7445d284e97ec5dafdd8f2741f496cac84ccda9as an example.

Suggestions for Certificate Issuers: Make it easier to find where to report abuse. Strengthen your verification methods. Don’t make getting certificates easier because of market pressures: the reputation of your brand is at stake.

Conclusion

Impostors regularly obtain authenticode certificates by disguising themselves as companies in any industry and any country. They will continue to acquire these certificates for as long as the malware industry demands it. If you see an authenticode certificate being abused, don’t hesitate to report it. It won’t damage a small business’ software deployment. It will only damage the business of an impostor.

Post Script: Loose Ends

The following are a few worthy tidbits that didn’t make it in elsewhere in the report.

When an actor impersonates a company, they may get certificates from multiple certificate providers. Within the 100 certificates, we saw 3 organizations who were issued certificates from two certificate providers. I am not aware of any process of communication between certificate issuers to identify these abuses.

From the 100 certificates, there were 3 companies which I was unable to confidently identify in government databases. There were another 4 companies where I was able to find a government registration, but unable to discover the industry.

Since certificates get abused by multiple actors, retroactively searching on abused certificates can potentially help researchers find new or unreported malware.

Where are the actual certificate details?

If you are interested in the raw certificate details, please contact me. Due to these organizations being impersonated, I’ve limited the direct references to these organizations within the blog-post, but I am willing to share the information privately.

Great post! Very informative! Super interesting to learn about how they get the certs. As I was reading this I was thinking “What can I do to contribute?”. I look forward to using your certReport tool in the near future!

Also, congrats on this tremendous 100th cert milestone!

LikeLiked by 1 person